The PDF You Got Back

If you've ever commissioned a security assessment, you probably got back a PDF summary, along with a handful of issues filed away in your ticketing system. You were left wondering

did they actually look at this thing?

If you're responsible for the security of embedded systems, building automation, or other networked devices, this question matters more than most reports will admit.

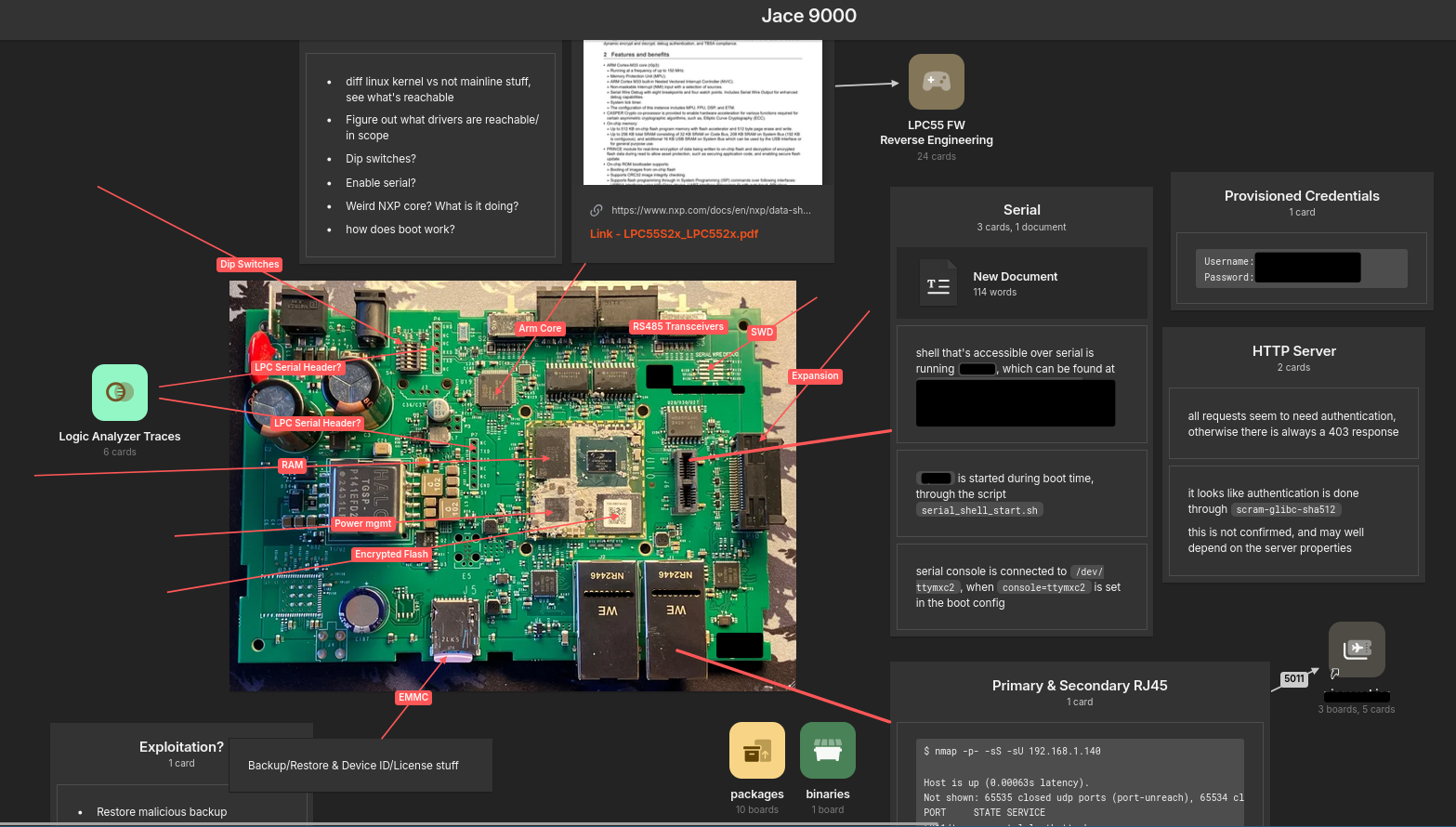

Our target: a Tridium Jace 9000 building automation controller.

The device itself matters less than the approach. It all begins with attack surfaces.

Doors, Windows, and Ladders

You're standing in front of a house. You want to get inside.

Nearly every reader just imagined a front door. Some of you might have also pictured a patio door, or maybe the first floor windows. A select few of you may have even imagined a ladder leading up to the second story windows.

Congratulations, you just performed a simplified version of an attack surface survey. Security professionals use this process to identify all interaction points that may allow someone to transition from outside to inside the house. These transition points are called security boundaries.

Network interfaces, USB ports, and debug headers are a device's doors and windows. Some are obvious; some require a ladder. Every security assessment should begin with enumerating the target's attack surface in some fashion.

We call assessments that skip this step "drive-by assessments": engagements that test what's obvious, report what's easy, and leave everything else unexamined.

Mapping the Jace 9000

Before touching firmware or running a single network scan, we build a complete map of how the device can be interacted with - physically and logically.

Enter the Jace 9000. Below is the raw attack surface notes that we build out during the start of every assessment.

When you first look at a board like this, your eye naturally goes to the biggest chip. That's the main SoC running Linux, the brain of the device. A drive-by assessment would start and end here.

We started there too - serial ports, network scans, the HTTP server. The map above captures all of it.

But we looked closer.

Reading the Board

Start with the obvious entry points.

Along the bottom edge: Ethernet ports that expose the HTTP API, SSH, and other system services. These also act as an IP/RS485 bridge in some ways (this device bridges both). Any network-centric assessment will find these surfaces.

Now the physical interfaces.

There's a daughter-board slot with a USB serial console, an SD card slot, expansion slots to the right, and what appears to be several serial console headers. These require physical access. Your first-floor windows. Still fairly obvious.

Then there's the RS485 ports.

These are somewhat remotely reachable. Typically the RS485 bus in a building management system is physically protected. You can't just get on the building's Wifi and hit these, as they must pass through bridge devices that (hopefully) are on a segmented IP network.

But, you may still be able to access this bus through the peripheral devices that run the building's environmental system.

Where does this bus lead?

Above and to the left of the main SOC lies an innocent-looking secondary chip - an LPC microcontroller. At first glance, it looks like a support component. Maybe some auxiliary function.

A drive-by assessment wouldn't give it a second thought.

We did.

The Chip Other Firms Would Miss

After extracting the main SoC's firmware, we found what you'd expect from a modern embedded Linux device: system services, a web application stack, mostly written in Go and Java (both memory-safe). Not impossible to find bugs.

But that LPC chip kept nagging at us.

What was it actually doing?

We traced the board connections and found RS485 transceivers feeding into the LPC. That's a serial protocol commonly used for industrial control systems, including BACnet, the building automation protocol this device speaks.

After extracting the LPC's firmware and reverse engineering it, we found our answer: this tiny chip is doing BACnet frame parsing. Raw protocol data comes in over RS485, gets parsed and validated by the LPC, then shuttles across an internal USB bus to the main SoC. The Linux kernel exposes these processed frames through a device interface for userland processes to consume.

And the LPC firmware? Looks to be written in C.

Upstream of Everything

That LPC chip is doing complex protocol parsing, in C, on data that arrives over the building network. It sits upstream of everything else, before the main SoC, before the Linux kernel, before any of the memory-safe application code that a typical assessment would focus on.

This isn't an edge case. This pattern (complex, memory-unsafe parsing pushed into "support" microcontrollers) shows up across industrial and embedded devices. A drive-by assessment would have spent all its time on the Java web server, while this thing sat there waiting.

How to Spot a Drive-By

Drive-by assessments treat security as a transaction: you pay, they scan and audit, you get a PDF or list of tickets. This is the norm in the security industry.

The alternative is treating the engagement as an investment in understanding.

Here's how to tell which one you got:

No map of what wasn't covered

If the report doesn't tell you what they didn't look at, they don't know either. The value of an assessment isn't just what was found. It's knowing what was checked and what wasn't. An illumination of the "unknown unknowns" so to speak.

No matter the depth of the assessment, a decent hacker can always tell you what paths they didn't cover.

Findings disconnected from your risk

A list of vulnerabilities ranked by CVSS isn't analysis. It's honestly just data entry. Real assessments connect findings to your threat model, your deployment, your business.

Anything else is just noise. For security to be a profitable endeavor for organizations, there must be a high-quality and actionable signal for your engineering department to use. Otherwise there isn't clarity, and you will just waste valuable resources trying to understand your results.

Nothing left behind

When the engagement ends, so does the security work. No tooling. No fuzz harnesses. No process improvements. You're paying for a snapshot, not durable security improvements.

Four Questions to Ask

When you get your next assessment back, don't just count findings.

Ask what they didn't cover: If they can't tell you, they don't know either.

Ask what their process was: Did they speed-run this assessment, or did they actually map the terrain? What's the story behind the results they're delivering to you?

Ask what's left for next time: A good assessment leaves you with a roadmap and durable improvements, not just a snapshot.

If your security vendor can't tell you about the LPC chip, they didn't really look.